I've been using WordPress as my blog tool everywhere but here. I've experimented with modifying the themes used. On ZeroIntelligence.net and on Never Another Job, I simply used themes I found on the Internet with some minor modifications to things like graphics and exactly what appears where in the sidebars.

More recently, I added a blog in a subdirectory for my BNI chapter. At the time of this writing, though, it's not live yet because nobody but me has actually written anything, which would then seem very silly. Nonetheless, by starting with this alternate home page, you could see that working. All the core pages, though, use basic HTML except for a couple of PHP calls to list articles. It's only a partial integration.

Tonight, though, for the first time I took a layout I'd done for a client and chopped it into a theme for WordPress. Applying this theme lets me set up WordPress and a full-fledged content management tool, one that's easy enough that there's hope my clients (this one and others) will be able to update things on their own. I expect to do this several more times, for other clients and for my own Heatherstone site.

Mucking about in PHP code and lots of CSS has been fascinating. You don't run into PHP at Microsoft!

Showing posts with label Work and Business. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Work and Business. Show all posts

Wednesday, June 27, 2007

Sunday, November 05, 2006

Contrast

I've been doing some thinking lately about the value of contrast, primarily about how it is an important tool in developing or marketing a new product. Contrast adds interest, so contrast is common in things to which we find ourselves drawn.

I'm using contrast here in a very broad sense, where it means that there are any two attributes of a single thing that are significantly different. Consider some examples, beginning with what we eat. Almost every meal we eat includes two or more foods. There really isn't any reason beyond getting a wide variety of nutrients not available in a single food for us to prepare multiple foods when we eat. However, even if it covered every element of nutrition you needed, you would be unlikely to feel particular satisfied by eating the same single item with every meal.

Another very basic example is that we tend not to design objects to be of a single color. My laptop, on which I'm typing this now, has a number of buttons that when they are in the "on" position light up with a blue glow. The blue contrasts with the black of the plastic and is therefore pleasing.

Not every example is so trivial, though. While it may not have such a firm grip on its market as it once did, Monster was remarkable in the job listing website business because of the contrast between the generally serious matter of browsing through jobs and the more whimsical nature of cartoon monsters adorning the pages. Similarly, "Amazon" (at least to me) conjures up images of a rain forest where the only inhabitants have little if anything in the way of a written language, which contrasts heavily with the concept of an online bookstore. I've noticed Elizabeth regularly browsing a make-up site called "Beauty Whore." Whatever you might feel about the name itself, it is certainly striking and memorable.

Even the name I picked for my online alter-ego, Dark Tortoise, was picked in part because of the contrast between "dark" and "tortoise." If asked to name a bunch of things that are dark, especially if given the "sinister" definition of the word, it's unlikely that "tortoise" would show up on your list anywhere in the top thousand.

I've been talking to my realtor friend, Ben, about ideas for a real estate website. Most such sites are, in my opinion, largely forgettable. They also tend to highlight the realtor, leaving the houses listed for sale as pretty much a set of photos and some basic attributes, like number of bedrooms and bathrooms. Buying a home, though, is largely an emotional decision with the house itself at the center of that decision. Thinking about contrast and that emotional factor suggests new ideas of how to present homes in an appealing, remarkable, and memorable way.

For example, we could present the homes almost as though they were people themselves so that the website visitor has the opportunity to be introduced to the homes and find one with a pleasing personality. We could include things like video testimonials about the houses given by either the developer or architect for new houses or the previous owners for resales. The presentation could even be made to look much like a typical (but well-designed) customized profile page on social networking sites like MySpace or FaceBook. The contrast between an inanimate object and the anthropomorphizing of that object would be unusual and notable.

Contrast, while not the only tool for creating distinction, seems a critical one. How could you apply new contrast to make something in your life more interesting, either to yourself or others as appropriate?

I'm using contrast here in a very broad sense, where it means that there are any two attributes of a single thing that are significantly different. Consider some examples, beginning with what we eat. Almost every meal we eat includes two or more foods. There really isn't any reason beyond getting a wide variety of nutrients not available in a single food for us to prepare multiple foods when we eat. However, even if it covered every element of nutrition you needed, you would be unlikely to feel particular satisfied by eating the same single item with every meal.

Another very basic example is that we tend not to design objects to be of a single color. My laptop, on which I'm typing this now, has a number of buttons that when they are in the "on" position light up with a blue glow. The blue contrasts with the black of the plastic and is therefore pleasing.

Not every example is so trivial, though. While it may not have such a firm grip on its market as it once did, Monster was remarkable in the job listing website business because of the contrast between the generally serious matter of browsing through jobs and the more whimsical nature of cartoon monsters adorning the pages. Similarly, "Amazon" (at least to me) conjures up images of a rain forest where the only inhabitants have little if anything in the way of a written language, which contrasts heavily with the concept of an online bookstore. I've noticed Elizabeth regularly browsing a make-up site called "Beauty Whore." Whatever you might feel about the name itself, it is certainly striking and memorable.

Even the name I picked for my online alter-ego, Dark Tortoise, was picked in part because of the contrast between "dark" and "tortoise." If asked to name a bunch of things that are dark, especially if given the "sinister" definition of the word, it's unlikely that "tortoise" would show up on your list anywhere in the top thousand.

I've been talking to my realtor friend, Ben, about ideas for a real estate website. Most such sites are, in my opinion, largely forgettable. They also tend to highlight the realtor, leaving the houses listed for sale as pretty much a set of photos and some basic attributes, like number of bedrooms and bathrooms. Buying a home, though, is largely an emotional decision with the house itself at the center of that decision. Thinking about contrast and that emotional factor suggests new ideas of how to present homes in an appealing, remarkable, and memorable way.

For example, we could present the homes almost as though they were people themselves so that the website visitor has the opportunity to be introduced to the homes and find one with a pleasing personality. We could include things like video testimonials about the houses given by either the developer or architect for new houses or the previous owners for resales. The presentation could even be made to look much like a typical (but well-designed) customized profile page on social networking sites like MySpace or FaceBook. The contrast between an inanimate object and the anthropomorphizing of that object would be unusual and notable.

Contrast, while not the only tool for creating distinction, seems a critical one. How could you apply new contrast to make something in your life more interesting, either to yourself or others as appropriate?

Wednesday, July 05, 2006

Agreeing to Stupid Things

Buck just left the office, headed to pick up a directory that's being returned to us by a customer that doesn't want it. They asked if someone could pick it up, probably just to save themselves the shipping cost to return it, and since it was over on Capitol Hill, near Buck's home, he agreed. Of course, just two minutes later, he realized that was not a very cost-effective way to handle the problem. Telling them to throw it away (or better, keep it with our compliments) would have been better. But Buck said that since he agreed to go pick it up he feels obligated to do so.

Sometimes we agree to do stupid things. Following through anyway is what shows character.

Sometimes we agree to do stupid things. Following through anyway is what shows character.

Monday, June 19, 2006

The Reason for Employment Law

We have had the unfortunate need of late to engage the services of an employment attorney, in this case to resolve a dispute with a disgruntled employee. This led, among other things, to this exchange:

Me: Is all employment law about covering your ass?

Attorney: Much of it is, I fear.

Me: Is all employment law about covering your ass?

Attorney: Much of it is, I fear.

Friday, June 16, 2006

Incentives

Buck and I have been having a lot of discussions about incentives in the workplace, such as bonuses, awards, and the like. It started from an article by Joel Spolsky on his Joel on Software website in the midst of a lot of changes in the company, include attrition of most of the staff.

My first reaction was "Bah!" Spolsky has lots of internal motivation, so the idea that he is not motivated by stuff like bonuses or awards. My recollection is that in addition to being a hotshot programmer, including at Microsoft for awhile, he's been an Israeli paratrooper or some such thing. His view of what motivates people has to be skewed from the majority.

Buck's pushing came in handy. He went on to read some of the references Spolsky listed. The main guy behind the "rewards are bad" movement is a research named Alfred "Alfie" Kohn. He's written plenty on the subject, including the fairly good synopsis, "For Best Results, Forget the Bonus."

I won't go into all the nitty-gritty detail here, but the essence of where we've settled is this:

I like where this is going. A year or two from now, we'll see if Kohn is right.

My first reaction was "Bah!" Spolsky has lots of internal motivation, so the idea that he is not motivated by stuff like bonuses or awards. My recollection is that in addition to being a hotshot programmer, including at Microsoft for awhile, he's been an Israeli paratrooper or some such thing. His view of what motivates people has to be skewed from the majority.

Buck's pushing came in handy. He went on to read some of the references Spolsky listed. The main guy behind the "rewards are bad" movement is a research named Alfred "Alfie" Kohn. He's written plenty on the subject, including the fairly good synopsis, "For Best Results, Forget the Bonus."

I won't go into all the nitty-gritty detail here, but the essence of where we've settled is this:

- The average base pay is significantly higher than it was six months ago.

- There is no annual performance review. Instead, we have weekly one-on-one's and make sure that performance, good and bad, is addressed no less frequently than that. Usually, it doesn't have to even come up, but that assures there's a forum for it when needed.

- There is an annual salary adjustment discussion where cost-of-living, changes in responsibilities, and changes in skills, training, and experience are addressed and a new salary is set for the next year.

- There are no bonuses or awards.

- Celebrations, like a company-wide party for the shipping of a new book, make a lot of sense, as they are not tied to individual performance.

- An employee dividend will be proposed to shareholders (and I believe there is substantial support for it,) but again not tied to individual performance, but instead to company performance. A share of profits will be set aside to distribute to all (salaried) employees. Since salary already addresses varying individual contributions, this is split equally.

I like where this is going. A year or two from now, we'll see if Kohn is right.

Sunday, May 07, 2006

Getting to Yes

I've just finished a much-recommended book, Getting to Yes, by Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton of the Harvard Negotiation Project. It turns out to be as good as expected, which is fantastic, since expectations were suitably high. I've previously read Difficult Conversations, another HNP book, and found it similarly valuable.

For those that haven't read the book, it lays out a method of what they call "principled negotiation." This is an alternative to the classic "positional negotiation" that's little more than starting at two extremes and haggling to some center point with little regard for what makes sense. They also point out that positional negotiation can also be less adverserial, although possibly just as destructive, when one or both negotiators are falling over each other to make concessions in the interests of protecting the relationship, such as when a boyfriend "gives in" to his girlfriend, despite what he really wants.

The authors cover four basic aspects to the method then relate how to use the method even if others in the negotiation aren't. As with Difficult Conversations, they include plenty of examples and one of the impressive aspects is that those examples range from a husband and a wife figuring out a floor plan for a custom home to the Camp David Accords.

Like many of the best books in the self-improvement and business categories, much of what's in the book will be familiar. ("I suggest that the only books that influence us are those for which we are ready, and which have gone a little further down our particular path than we have gone ourselves." - E M Forster)

We've all negotiated with others many, many times and had varying levels of success. The successful negotiations often included inadvertent or instinctive reliance on some aspects of these methods. But the complete method described in Getting to Yes brings it all together, explaining why some negotiations have failed and how others could have gone better.

In just the last few days, I've already had several opportunities to start practicing the techniques from figuring out what to have for dinner to improving the possibilities for two deals that my company is seeking to make with other companies - one as a vendor, one as a customer. As such, I can't help but pile on the bandwagon and recommend this book as what ought to be required reading. If you haven't read it, you need to, and not just for work. If you have kids, you need to get them to read it, too, as I think it will be one of those things that prepares them for adulthood more than anything they will learn in school.

For those that haven't read the book, it lays out a method of what they call "principled negotiation." This is an alternative to the classic "positional negotiation" that's little more than starting at two extremes and haggling to some center point with little regard for what makes sense. They also point out that positional negotiation can also be less adverserial, although possibly just as destructive, when one or both negotiators are falling over each other to make concessions in the interests of protecting the relationship, such as when a boyfriend "gives in" to his girlfriend, despite what he really wants.

The authors cover four basic aspects to the method then relate how to use the method even if others in the negotiation aren't. As with Difficult Conversations, they include plenty of examples and one of the impressive aspects is that those examples range from a husband and a wife figuring out a floor plan for a custom home to the Camp David Accords.

Like many of the best books in the self-improvement and business categories, much of what's in the book will be familiar. ("I suggest that the only books that influence us are those for which we are ready, and which have gone a little further down our particular path than we have gone ourselves." - E M Forster)

We've all negotiated with others many, many times and had varying levels of success. The successful negotiations often included inadvertent or instinctive reliance on some aspects of these methods. But the complete method described in Getting to Yes brings it all together, explaining why some negotiations have failed and how others could have gone better.

In just the last few days, I've already had several opportunities to start practicing the techniques from figuring out what to have for dinner to improving the possibilities for two deals that my company is seeking to make with other companies - one as a vendor, one as a customer. As such, I can't help but pile on the bandwagon and recommend this book as what ought to be required reading. If you haven't read it, you need to, and not just for work. If you have kids, you need to get them to read it, too, as I think it will be one of those things that prepares them for adulthood more than anything they will learn in school.

Friday, April 21, 2006

Questioning Assumptions

A big part of my role at Columbia Books, especially during these early days (it's so hard to believe I only started 11 weeks ago!) has been to question assumptions. These have been big things, like whether or not we should continue elements of our existing product line or whether we really need to be located in DC, and little things, like whether we have the right phone service or need to have a stamp machine. It's exciting stuff and whether I look at the assumptions and decide that a particular one is good and leave things at the status quo or decide it's bad and initiate a change, the result produces confidence that we're doing the right thing.

An example: We have a Pitney Bowes stamp machine, but around the time I started, it had broken down. It was brought to my attention as something that we needed to fix, but by questioning the assumption as to whether we needed such a machine and the associated costs, I decided to let it sit for awhile. After a month of the machine sitting there broken and with not one complaint, it seemed likely we didn't really need it. We had a big mailing that we did for renewals on one of our products around then and prepared it with stamps and the help of my daughter, Katerina, and Debra's daughter, Natalie. We only do three or four of those a year. I've cancelled the contract and we're returning the machine, saving the company a small but significant amount of money.

This questioning of assumptions and the accompanying review of a given status quo is something I've always done regularly in my work. The decisions I make today will be questioned again, by me or whoever might be delegated responsibility for the subject matter, at appropriate intervals, whether months or years.

In my personal life, though, I'm not sure I've done enough of this. Obviously, I must have done some questioning, since I've moved from small business to big business and back again, as one of the larger examples. But when I think about other assumptions I have, I realize there are many that have gone unquestioned. For example:

An example: We have a Pitney Bowes stamp machine, but around the time I started, it had broken down. It was brought to my attention as something that we needed to fix, but by questioning the assumption as to whether we needed such a machine and the associated costs, I decided to let it sit for awhile. After a month of the machine sitting there broken and with not one complaint, it seemed likely we didn't really need it. We had a big mailing that we did for renewals on one of our products around then and prepared it with stamps and the help of my daughter, Katerina, and Debra's daughter, Natalie. We only do three or four of those a year. I've cancelled the contract and we're returning the machine, saving the company a small but significant amount of money.

This questioning of assumptions and the accompanying review of a given status quo is something I've always done regularly in my work. The decisions I make today will be questioned again, by me or whoever might be delegated responsibility for the subject matter, at appropriate intervals, whether months or years.

In my personal life, though, I'm not sure I've done enough of this. Obviously, I must have done some questioning, since I've moved from small business to big business and back again, as one of the larger examples. But when I think about other assumptions I have, I realize there are many that have gone unquestioned. For example:

- Do I care about whether I own or rent?

- What time should I go to sleep?

- When should I get up?

- Do I have the right hobbies, too many hobbies, too few?

- Should I really have a television or an Xbox?

- Is my car worth the payments?

- Should I plan my future more? How about less?

Thursday, April 06, 2006

Thinking Hourly

One of the things I find the most frustrating in a work environment is when people are paid a salary, yet think hourly. "Thinking hourly" results in work schedules that have all kinds of contortions in them, like short lunches, early arrival, early departure, time out of the office, and the largely ineffective "work from home."

I personally prefer people take normal lunch hours, for example, and take at least some of their lunches with coworkers, especially coworkers that don't do the exact same job. That's the kind of thing that can spark new ideas, new enthusiasm, awareness of a bigger picture, and so on. People thinking hourly often shorten their lunch hour to a lunch half-hour or even less, then eat at their desk, all in an effort to thereafter leave early.

Of course, not everyone cares about their job enough to want to minimize their actual hours. Plenty of people only go to work to get the check and get out. I happen to not be one of those - I love my job and it's an important part of my life. I respect the point of view of those where it's not that way.

The real kicker, though, is when bonus time comes and the hourly thinker is surprised or angry that he doesn't get one. Hourly thinking also results in a clear exchange of labor for money. A person very careful to only give the exact amount of arranged labor should only receive the exact amount of arranged pay. Bonuses should be in recognition of something more from the employee.

I wonder how many people approach their jobs with hourly thinking and how many don't.

I personally prefer people take normal lunch hours, for example, and take at least some of their lunches with coworkers, especially coworkers that don't do the exact same job. That's the kind of thing that can spark new ideas, new enthusiasm, awareness of a bigger picture, and so on. People thinking hourly often shorten their lunch hour to a lunch half-hour or even less, then eat at their desk, all in an effort to thereafter leave early.

Of course, not everyone cares about their job enough to want to minimize their actual hours. Plenty of people only go to work to get the check and get out. I happen to not be one of those - I love my job and it's an important part of my life. I respect the point of view of those where it's not that way.

The real kicker, though, is when bonus time comes and the hourly thinker is surprised or angry that he doesn't get one. Hourly thinking also results in a clear exchange of labor for money. A person very careful to only give the exact amount of arranged labor should only receive the exact amount of arranged pay. Bonuses should be in recognition of something more from the employee.

I wonder how many people approach their jobs with hourly thinking and how many don't.

Friday, December 23, 2005

Clever Discounting

I went into a jewelry store today that had big signs out front reading, "Up to 70% off!" Inside, most of the displays were labeled with "Everything here 50%, plus an additional 20%!" At first blush, that's 70%, right?

Wrong. Since the 20% is taken off after the 50% off has been calculated, the 20% only applies to half the retail price. That is, 10% of retail, which makes the item actually 60% off, a perfectly valid amount in "Up to 70%."

60% off was a perfectly good discount for the item I purchased, and while I'd prefer 70% off, that 10% was in some ways worth observing the cleverness of the discounting scheme. Caveat emptor!

Wrong. Since the 20% is taken off after the 50% off has been calculated, the 20% only applies to half the retail price. That is, 10% of retail, which makes the item actually 60% off, a perfectly valid amount in "Up to 70%."

60% off was a perfectly good discount for the item I purchased, and while I'd prefer 70% off, that 10% was in some ways worth observing the cleverness of the discounting scheme. Caveat emptor!

Thursday, December 01, 2005

Next, Build a Great Team

In a previous post, I wrote about picking the right person for a task. The process scales up for looking at a team and analyzing what the team should do and who the next hire should be. The first step is to take a look at every task the team does or should be doing today. This will be, by necessity, a fairly high level task area. “Update screenshots based on feedback” is too narrow a task. “Write specifications” is about right. If the list is more than about 10-15 tasks, you’re probably defining the tasks too narrowly, dealing with a team larger than what I’m considering here (that is, a workgroup of up to about 10 people,) or your team is way over-committed. I’ll discuss the latter two problems in a moment, but for this first step, you should make sure you have broad categories.

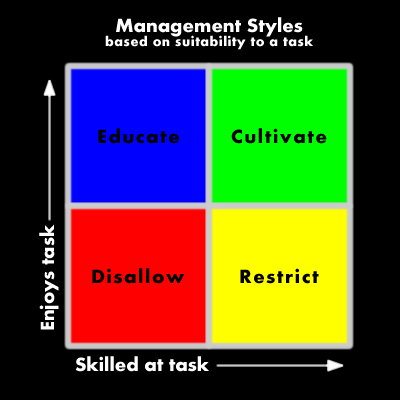

Next, go through the suitability exercise for each member of the team for each task the team does, figuring out what each member likes and how skilled he is at the task. This fills a matrix that allows you to cross-reference tasks and team members and tell at a glance where the strengths and weakness of the team are. I’ve created a fairly simply sample matrix for a team with three people and four general tasks so we have a basis for discussion.

On this chart, “++” represents “Cultivate,” “+” represents “Educate”, “-“ is for Restrict, and Disallow is blank.

When presented this way, the nature of the team practically leaps from the page. Let’s discuss some specifics anyway. The person that should take on a leadership role for each of the first three tasks is clear. Bob should focus on requirements, Joe on specifications, and Mary on presentations. There’s no need to ask Mary to spend much time on requirements, despite her skill in that area, because Bob has it covered and Joe wants to learn. The whole team is well equipped to produce specifications, which is very good, since I based this loosely on a program management team where that’s the top priority.

Asking Bob to present for executives would be a very bad idea. So much better would be to ask Joe to be a presenter, but have him work with Mary to prepare the presentation. Mary gets the opportunity to be a leader and mentor, but Joe gets to grow his skills. With this particular mix, we have a great situation because Joe gets to lead on specification writing, and Mary gets the growth opportunity (along with Bob.)

The team clearly has a problem in the support area, though. There are two skilled individuals, but it’s a part of the job that neither of them really want to do. Asking them to do it, despite all the other good stuff they will get to do, is going to be a source of friction. There’s two ways a manager can handle this. First of all, he can try to shed that responsibility altogether. In a larger organization, this may well be possible, and the example certainly suggests there are other teams around based on the nature of the tasks. Attacking the problem with concerns about team morale and building stronger focus for the team would be good, defensible arguments. In effect, we’re addressing the concern about the team being overcommitted that I mentioned above.

Another solution is to hire the next addition to the team and use the need for a good support person as a way to qualify candidates. In fact, a person with a “Cultivate” level of support suitability and an interest in either presentation or requirements skills would actually be a great addition to the team, even if they hate writing specifications. For a program management team, this would not be obvious without going through an exercise like this.

This process is scalable beyond the workgroup level. If you roll up the overall team into a single team suitability column, you’ll get “Educate” (or maybe “Educate+” if I can slightly mangle my own methodology) for the first three tasks and “Restrict” for last. Also, in the example, the first three items could perhaps be rolled up into “Program Management” with an “Educate” suitability level. If the larger organization that contains this team does the exercise across teams against a task level where the tasks have been rolled up into more general groupings like this, similar analysis at the workgroup level can be done. There’s no reason that the columns can’t represent whole divisions or that the task rows can’t represent lines of business, it just takes more work to do the bottom up accumulation of data.

If any of my readers has an opportunity to try this out with a team, I would be very interested in hearing about what you find out and how this has allowed you to change the team for the better.

Next, go through the suitability exercise for each member of the team for each task the team does, figuring out what each member likes and how skilled he is at the task. This fills a matrix that allows you to cross-reference tasks and team members and tell at a glance where the strengths and weakness of the team are. I’ve created a fairly simply sample matrix for a team with three people and four general tasks so we have a basis for discussion.

On this chart, “++” represents “Cultivate,” “+” represents “Educate”, “-“ is for Restrict, and Disallow is blank.

When presented this way, the nature of the team practically leaps from the page. Let’s discuss some specifics anyway. The person that should take on a leadership role for each of the first three tasks is clear. Bob should focus on requirements, Joe on specifications, and Mary on presentations. There’s no need to ask Mary to spend much time on requirements, despite her skill in that area, because Bob has it covered and Joe wants to learn. The whole team is well equipped to produce specifications, which is very good, since I based this loosely on a program management team where that’s the top priority.

Asking Bob to present for executives would be a very bad idea. So much better would be to ask Joe to be a presenter, but have him work with Mary to prepare the presentation. Mary gets the opportunity to be a leader and mentor, but Joe gets to grow his skills. With this particular mix, we have a great situation because Joe gets to lead on specification writing, and Mary gets the growth opportunity (along with Bob.)

The team clearly has a problem in the support area, though. There are two skilled individuals, but it’s a part of the job that neither of them really want to do. Asking them to do it, despite all the other good stuff they will get to do, is going to be a source of friction. There’s two ways a manager can handle this. First of all, he can try to shed that responsibility altogether. In a larger organization, this may well be possible, and the example certainly suggests there are other teams around based on the nature of the tasks. Attacking the problem with concerns about team morale and building stronger focus for the team would be good, defensible arguments. In effect, we’re addressing the concern about the team being overcommitted that I mentioned above.

Another solution is to hire the next addition to the team and use the need for a good support person as a way to qualify candidates. In fact, a person with a “Cultivate” level of support suitability and an interest in either presentation or requirements skills would actually be a great addition to the team, even if they hate writing specifications. For a program management team, this would not be obvious without going through an exercise like this.

This process is scalable beyond the workgroup level. If you roll up the overall team into a single team suitability column, you’ll get “Educate” (or maybe “Educate+” if I can slightly mangle my own methodology) for the first three tasks and “Restrict” for last. Also, in the example, the first three items could perhaps be rolled up into “Program Management” with an “Educate” suitability level. If the larger organization that contains this team does the exercise across teams against a task level where the tasks have been rolled up into more general groupings like this, similar analysis at the workgroup level can be done. There’s no reason that the columns can’t represent whole divisions or that the task rows can’t represent lines of business, it just takes more work to do the bottom up accumulation of data.

If any of my readers has an opportunity to try this out with a team, I would be very interested in hearing about what you find out and how this has allowed you to change the team for the better.

Monday, November 28, 2005

Picking the Right Person for a Task

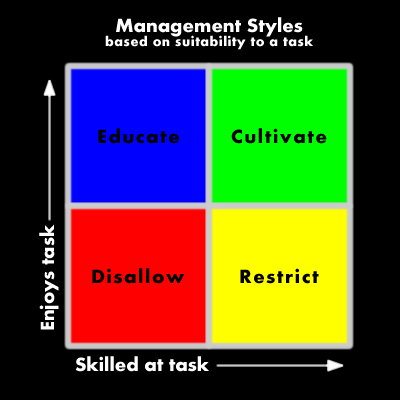

In thinking about how you pick the right person for a given task, a good way to figure it out is to consider two axes of suitability. The first is whether the person is any good at the task. The second is whether the person likes the task. These are really pretty obvious, but let’s consider what happens when you take both and map the person’s suitability into one of the four quadrants formed by the options. I’ve given each quadrant a name for easy reference in discussion, where the name defines what you as a manager should do with regard to assigning the work to a person who’s suitability falls in that quadrant.

Cultivate: A manager should do this for a person that both likes the task and is good at it. Not only does this mean that you have a great choice of who should be assigned the task, if you are a manager of this person, you should be looking for opportunities to leverage his skills to do more of this and related work. In conjunction with his individual contribution, you should also be looking for ways he can supply leadership to others, assuming of course that he isn’t someone who shies away from leadership entirely. I think that latter case is fairly rare, as leadership doesn’t have to mean management or public speaking, but can take many forms.

Educate: This is what you do for a person that likes the task but does not yet have competency. I used “educate” rather than “train” because education can be more than just training. Education should include training; apprenticeship, where the person works with a more skilled coworker to learn the skills; guidance, where the manager or a mentor helps him figure out what he needs to do to improve; and opportunity, where he is given a chance to work his skills on the task, but probably off the critical path. The most important thing is to recognize this is where growth happens. An employee not doing anything that falls into this category is going to get bored, frustrated, or angry, depending on temperament and what other categories apply, and will either leave or stay on with negative impact on the larger team.

Restrict: Sometimes, a person is good at a task, but doesn’t like to do it. This is the most dangerous situation with regards to destroying a good manager/employee relationship because it’s easy for the manager to give the person the task and keep him on it. If at all possible, you shouldn’t ask him to do this work. If you do, though, it’s important to do several things: make it clear it’s temporary; explain the need; take immediate and visible steps to relieve him of the work; and find a way to deliver additional rewards for the work. Don’t think that the extra rewards will carry you along indefinitely, though. If he doesn’t like the work, you won’t be able to pay him enough to keep him at it for very long.

Disallow: For the person who doesn’t like a task and isn’t any good at it anyway, I was really thinking “avoid,” but the word isn’t strong enough. This one sounds obvious when you read it here, but managers assign work to people who don’t like it and aren’t good at it all the time. If you think your employee will grow to like it as he gains skill, think again. Not only will he hate the work, he’ll feel humiliated by his failures, disinterested in the improvement, and resentful of the assignment. If he was going to get better at it, he’d have expressed an interest. If you don’t have anyone else to do this work, then figure out how to get by without it until you have someone who can. If you decide it just can’t wait, then you have a problem on the order of figuring out which employee (or at least which employee relationship) you’re going to sacrifice to get the work done. Put in such terms, it’s likely you’ll reconsider the importance of the work one more time.

A matrix of tasks and the suitability levels for the employee assigned to each provides a pretty clear roadmap about how your employees’ careers can be directed for maximum success.

Cultivate: A manager should do this for a person that both likes the task and is good at it. Not only does this mean that you have a great choice of who should be assigned the task, if you are a manager of this person, you should be looking for opportunities to leverage his skills to do more of this and related work. In conjunction with his individual contribution, you should also be looking for ways he can supply leadership to others, assuming of course that he isn’t someone who shies away from leadership entirely. I think that latter case is fairly rare, as leadership doesn’t have to mean management or public speaking, but can take many forms.

Educate: This is what you do for a person that likes the task but does not yet have competency. I used “educate” rather than “train” because education can be more than just training. Education should include training; apprenticeship, where the person works with a more skilled coworker to learn the skills; guidance, where the manager or a mentor helps him figure out what he needs to do to improve; and opportunity, where he is given a chance to work his skills on the task, but probably off the critical path. The most important thing is to recognize this is where growth happens. An employee not doing anything that falls into this category is going to get bored, frustrated, or angry, depending on temperament and what other categories apply, and will either leave or stay on with negative impact on the larger team.

Restrict: Sometimes, a person is good at a task, but doesn’t like to do it. This is the most dangerous situation with regards to destroying a good manager/employee relationship because it’s easy for the manager to give the person the task and keep him on it. If at all possible, you shouldn’t ask him to do this work. If you do, though, it’s important to do several things: make it clear it’s temporary; explain the need; take immediate and visible steps to relieve him of the work; and find a way to deliver additional rewards for the work. Don’t think that the extra rewards will carry you along indefinitely, though. If he doesn’t like the work, you won’t be able to pay him enough to keep him at it for very long.

Disallow: For the person who doesn’t like a task and isn’t any good at it anyway, I was really thinking “avoid,” but the word isn’t strong enough. This one sounds obvious when you read it here, but managers assign work to people who don’t like it and aren’t good at it all the time. If you think your employee will grow to like it as he gains skill, think again. Not only will he hate the work, he’ll feel humiliated by his failures, disinterested in the improvement, and resentful of the assignment. If he was going to get better at it, he’d have expressed an interest. If you don’t have anyone else to do this work, then figure out how to get by without it until you have someone who can. If you decide it just can’t wait, then you have a problem on the order of figuring out which employee (or at least which employee relationship) you’re going to sacrifice to get the work done. Put in such terms, it’s likely you’ll reconsider the importance of the work one more time.

A matrix of tasks and the suitability levels for the employee assigned to each provides a pretty clear roadmap about how your employees’ careers can be directed for maximum success.

Tuesday, November 15, 2005

Haiku Status Report

Duncan, a developer on my feature team, was one of those I asked to give status in 30 words or less. He responded in haiku:

(Our bug database includes a priority field that the team that triages bugs tends to not set as they should.)

I am inspired to try using haiku for my own status reports in the future.

Many bugs lately!

Querying priority...

Oops, field is empty.

Querying priority...

Oops, field is empty.

(Our bug database includes a priority field that the team that triages bugs tends to not set as they should.)

I am inspired to try using haiku for my own status reports in the future.

Monday, September 26, 2005

Pleasant Surprise

My first meeting at work was a one-on-one with Chris. (For those that don't know, that's time where you and your manager, or in this case my "skip-level manager," get together to talk about things like career. With Michael, I meet weekly.) We have one scheduled for a half-hour every three months. That's two whole hours a year! Hmm. Sounds a little light, now that I mention it.

Anyway, Chris was a few minutes late and I was thinking that's kind of, well, lame, considering that we only get two hours a year and five minutes is just over 4% of that time. Yes, I actually did the math in my head while I waited in the hallway, which is why I didn't see his email saying he'd be late.

Then he shows up, we sit down in his office, and he says, "Hey, have you had breakfast? How about we go to the diner, 'cause I'm really hungry." He drove, we stopped at a bank so he could get cash, then we had breakfast. He paid for mine and took the time to talk through the biggest issue I face these days in my current job. The half-hour ended up being a catered hour-and-a-half. So my attribution of "lame" was completely misplaced. What a pleasant surprise. Seriously.

What I've really learned is that I need to make sure not to do that kind of attribution or pre-judgment in the future, but let the aggravation only happen after I know the whole story and determine that aggravation is truly warranted. Then, deal with it like an adult, not a petulant child. Sound like a plan?

Anyway, Chris was a few minutes late and I was thinking that's kind of, well, lame, considering that we only get two hours a year and five minutes is just over 4% of that time. Yes, I actually did the math in my head while I waited in the hallway, which is why I didn't see his email saying he'd be late.

Then he shows up, we sit down in his office, and he says, "Hey, have you had breakfast? How about we go to the diner, 'cause I'm really hungry." He drove, we stopped at a bank so he could get cash, then we had breakfast. He paid for mine and took the time to talk through the biggest issue I face these days in my current job. The half-hour ended up being a catered hour-and-a-half. So my attribution of "lame" was completely misplaced. What a pleasant surprise. Seriously.

What I've really learned is that I need to make sure not to do that kind of attribution or pre-judgment in the future, but let the aggravation only happen after I know the whole story and determine that aggravation is truly warranted. Then, deal with it like an adult, not a petulant child. Sound like a plan?

Wednesday, September 21, 2005

Mess with Their Heads

I got my sneakers really wet last night, so I needed to wear different shoes today. I wore dress shoes. Since I was going to wear dress shoes and a long-sleeved shirt anyway, I went ahead and wore dressier pants, too, instead of my usual jeans.

That really messes with the heads of your managers. They have to be thinking, "Is he interviewing? Is he planning to leave?" I think it might even make them treat you just a bit better in the hopes that it will distract you from aspects of work that you find less than pleasant.

I also picked up the book "Difficult Conversations" today at Kevin's recommendation. It's subtitled, "How to Discuss What Matters Most." It occurs to me that even if I never read it or read it and learned nothing, just having it conspicuously on my desk could improve the tenor of conversations I have with co-workers because it at least looks like I'm trying to figure out how to work with them better.

I didn't set out to mess with their heads, but it's so easy I can't help but do it without trying.

That really messes with the heads of your managers. They have to be thinking, "Is he interviewing? Is he planning to leave?" I think it might even make them treat you just a bit better in the hopes that it will distract you from aspects of work that you find less than pleasant.

I also picked up the book "Difficult Conversations" today at Kevin's recommendation. It's subtitled, "How to Discuss What Matters Most." It occurs to me that even if I never read it or read it and learned nothing, just having it conspicuously on my desk could improve the tenor of conversations I have with co-workers because it at least looks like I'm trying to figure out how to work with them better.

I didn't set out to mess with their heads, but it's so easy I can't help but do it without trying.

Friday, September 16, 2005

At Work Today

Something overheard at work today: "You know, I come in before him and leave after him, and I'm not even working all that hard."

Saturday, September 03, 2005

Better Attitude About Review

It took me much less time to get past what I always see as terrible news with my annual review this year. That's surprising, because I was very disappointed with my final score at first. But then, I realized that getting a score that translates as "exceeded expectations" instead of "greatly exceeded expectations" really isn't so bad, especially when I work at one of the top software companies (and arguably one of the top companies period) in the world.

I've also received bonuses this year that exceed the U.S. poverty line for a family of three beyond my base pay, and a larger family than that if you include stock awards. I also received a raise that exceeded the estimated inflation rate for 2004. What is there in that such that complaining about it makes sense?

My manager's feedback on the review boils down to, "Dude, you are the awesome, but you really should learn to play nicer with others even when they annoy you, heck, even if they deserve it." It would be so cool if he just included that as a synopsis. I'm going to ask him to do so.

That's what I'll work on this coming year. Even if I personally produce less, I'll focus on getting less stressed out and making sure that those around me are more successful. An interesting side effect is that if I'm asked to cancel my plans and work some weekend, I'll be able to say, "No, that will make me very cranky and I don't get along with my peers as well when I'm cranky. I think I need to limit stuff like that."

I've also received bonuses this year that exceed the U.S. poverty line for a family of three beyond my base pay, and a larger family than that if you include stock awards. I also received a raise that exceeded the estimated inflation rate for 2004. What is there in that such that complaining about it makes sense?

My manager's feedback on the review boils down to, "Dude, you are the awesome, but you really should learn to play nicer with others even when they annoy you, heck, even if they deserve it." It would be so cool if he just included that as a synopsis. I'm going to ask him to do so.

That's what I'll work on this coming year. Even if I personally produce less, I'll focus on getting less stressed out and making sure that those around me are more successful. An interesting side effect is that if I'm asked to cancel my plans and work some weekend, I'll be able to say, "No, that will make me very cranky and I don't get along with my peers as well when I'm cranky. I think I need to limit stuff like that."

Thursday, September 01, 2005

Reviews

It is currently review time at Microsoft. We're actually at the tail end of that time because as of September 15th, if your manager hasn't given you your review, you'll find out what "your numbers" are anyway, as you'll get a paycheck that reflects the changes. The "numbers" consists of a review score, a stock award, a raise, a bonus, and perhaps a promotion. Review scores run from 2.5 to 5.0: 2.5 if you're about to be fired, 3.0 if you are considered a weak performer (although there are exceptions, like for people who just joined a team and despite HR discouragement of such a policy often get a 3.0,) 3.5 for reasonable good performance, 4.0 for great performance, and 4.5 or 5.0 if you had great performance and get lucky (or something.)

My group is running late. No one on my team knows their numbers yet, and that's kind of exasperating because we're two months into the next review cycle and don't have a clear idea of the rewards for the past review cycle. I should get mine tomorrow, though, and that will be at least one huge relief because I really don't need additional areas of uncertainty in my life right now - I have more than enough of those already.

Reviews also include a sort of essay by your manager about your performance was over the year. This may or may not correspond to the actual review score since usually your manager doesn't have any direct control over the score you get. For example, my last review reads like a 4.0 review, but I actually received a 3.5. In my experience, reviews, even good ones like my "tracking to 4.0" review mid-year (where some groups give a "tracking to" score that may or may not mean anything during the actual yearly review) are basically demoralizing. Such reviews usually include a basic statement of the good things you did, without going very deep on the subject, followed by a detailed and excruciating picking apart of what could have gone better. As such, I generally dislike the review process, despite getting continually better reviews since I started at Microsoft.

If I were to go back to my small business and have employees again, this is not how I would handle reviews. I would fall back on Peter Drucker's suggestions to keep reviews positive and save the negative stuff for coaching sessions along the way. Peter Drucker is one of the world's foremost experts on management and I trust his opinions on things of this nature.

One last thing I'll add is something Trevor said to me and others about writing reviews, gleaned from some study he's done on writing good reviews, something that makes darn good sense: "When writing a review, you should try to include words like 'expectations.' You should avoid using words like 'idiot.'"

My group is running late. No one on my team knows their numbers yet, and that's kind of exasperating because we're two months into the next review cycle and don't have a clear idea of the rewards for the past review cycle. I should get mine tomorrow, though, and that will be at least one huge relief because I really don't need additional areas of uncertainty in my life right now - I have more than enough of those already.

Reviews also include a sort of essay by your manager about your performance was over the year. This may or may not correspond to the actual review score since usually your manager doesn't have any direct control over the score you get. For example, my last review reads like a 4.0 review, but I actually received a 3.5. In my experience, reviews, even good ones like my "tracking to 4.0" review mid-year (where some groups give a "tracking to" score that may or may not mean anything during the actual yearly review) are basically demoralizing. Such reviews usually include a basic statement of the good things you did, without going very deep on the subject, followed by a detailed and excruciating picking apart of what could have gone better. As such, I generally dislike the review process, despite getting continually better reviews since I started at Microsoft.

If I were to go back to my small business and have employees again, this is not how I would handle reviews. I would fall back on Peter Drucker's suggestions to keep reviews positive and save the negative stuff for coaching sessions along the way. Peter Drucker is one of the world's foremost experts on management and I trust his opinions on things of this nature.

One last thing I'll add is something Trevor said to me and others about writing reviews, gleaned from some study he's done on writing good reviews, something that makes darn good sense: "When writing a review, you should try to include words like 'expectations.' You should avoid using words like 'idiot.'"

Wednesday, August 17, 2005

Don't Be That Guy

I went to a lecture today, "Getting Started in Podcasting." There were parts of it that were interesting although it certainly feels like there's a certain amount of much ado about nothing. Podcasting is mostly about recording some audio or video then posting it on the Internet. That's about it.

The thing is, part of the title is "Getting Started." It seems like there were several of "that guy" there, though. You know the one. He comes to the introductory session, but already knows all that stuff. Then, he doesn't just ask questions about advanced topics while the people sitting around him stare at him blankly, he peppers those questions with his own comments. Comments that effectively highjack the presentation so he can show how smart he is.

The first guy like this that I recall distinctly was in a college course in computer science. I forget the exact title of the class, but the examples were all written in Pascal. Almost every class session, and often multiple times in the same class session, he'd start his question or comment with, "Well, I use C and...." (For those that don't know, Pascal and C are two computer programming languages. Pascal was mostly used as an instructional language. C and its descendents are probably the most popular mainstream languages.) You could just hear it in the guy's voice that he thought he was just the coolest guy ever because he was in a college class and already was using C at work.

Eventually, whenever he'd be about to say something, I'd mutter under my breath, "Well, I use C and...." Seconds later he'd say it. When I say mutter, of course I mean "say quietly but not so quietly the half-dozen people around me couldn't hear me." It was all so entertaining for us, and way better than listening to that guy.

Don't be that guy.

The thing is, part of the title is "Getting Started." It seems like there were several of "that guy" there, though. You know the one. He comes to the introductory session, but already knows all that stuff. Then, he doesn't just ask questions about advanced topics while the people sitting around him stare at him blankly, he peppers those questions with his own comments. Comments that effectively highjack the presentation so he can show how smart he is.

The first guy like this that I recall distinctly was in a college course in computer science. I forget the exact title of the class, but the examples were all written in Pascal. Almost every class session, and often multiple times in the same class session, he'd start his question or comment with, "Well, I use C and...." (For those that don't know, Pascal and C are two computer programming languages. Pascal was mostly used as an instructional language. C and its descendents are probably the most popular mainstream languages.) You could just hear it in the guy's voice that he thought he was just the coolest guy ever because he was in a college class and already was using C at work.

Eventually, whenever he'd be about to say something, I'd mutter under my breath, "Well, I use C and...." Seconds later he'd say it. When I say mutter, of course I mean "say quietly but not so quietly the half-dozen people around me couldn't hear me." It was all so entertaining for us, and way better than listening to that guy.

Don't be that guy.

Thursday, August 11, 2005

Jack of All Trades

Yesterday, I finished up some SQL views that will allow our internal customers to create ad hoc reports about beta program participation. This is a task that had been languishing for some time, waiting for a developer to come available who could do the work. But now, I'm doing it.

At Microsoft, there are six general disciplines defined on a team: Program Management (feature design and schedules,) Product Management (requirements and customer interaction,) Development, Test, User Experience (usability, documentation, and interface design,) and Release Management (deployment.)

With the work I just did for these views, it's my first work as a developer at Microsoft. My primary role is as a program manager. We don't have a dedicated product manager, so we're light on representation there, so I've picked up some of that work, too. I've filed as many bugs as anyone on the test team and have even had some days where my bug report total exceeds that of the entire test team combined. And I recently contributed as editor for our administration site's documentation. When we were deploying, I worked with the Passport team to make sure our site met compliance. That means I've now done some work in every discipline. And that is cool.

At Microsoft, there are six general disciplines defined on a team: Program Management (feature design and schedules,) Product Management (requirements and customer interaction,) Development, Test, User Experience (usability, documentation, and interface design,) and Release Management (deployment.)

With the work I just did for these views, it's my first work as a developer at Microsoft. My primary role is as a program manager. We don't have a dedicated product manager, so we're light on representation there, so I've picked up some of that work, too. I've filed as many bugs as anyone on the test team and have even had some days where my bug report total exceeds that of the entire test team combined. And I recently contributed as editor for our administration site's documentation. When we were deploying, I worked with the Passport team to make sure our site met compliance. That means I've now done some work in every discipline. And that is cool.

Monday, August 01, 2005

Low Importance = High Interest

I've noticed that when I send or receive email marked with "Low Importance" it's actually another way to mark the email as particularly interesting. In essence, "It's low importance? Oh, then it's probably something personal or otherwise much more intriguing than a simple work-related message."

Do you read low importance messages before normal importance messages? Before high importance messages?

Do you read low importance messages before normal importance messages? Before high importance messages?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)